The mine warfare began in 1916.

Given the impossibility of conquering the emplacements of the enemy, both armies dug the mountain, built tunnels to place explosive under the enemy's emplacements and blow them up. Four Austrian mines and a great Italian mine exploded on the Lagazuoi.

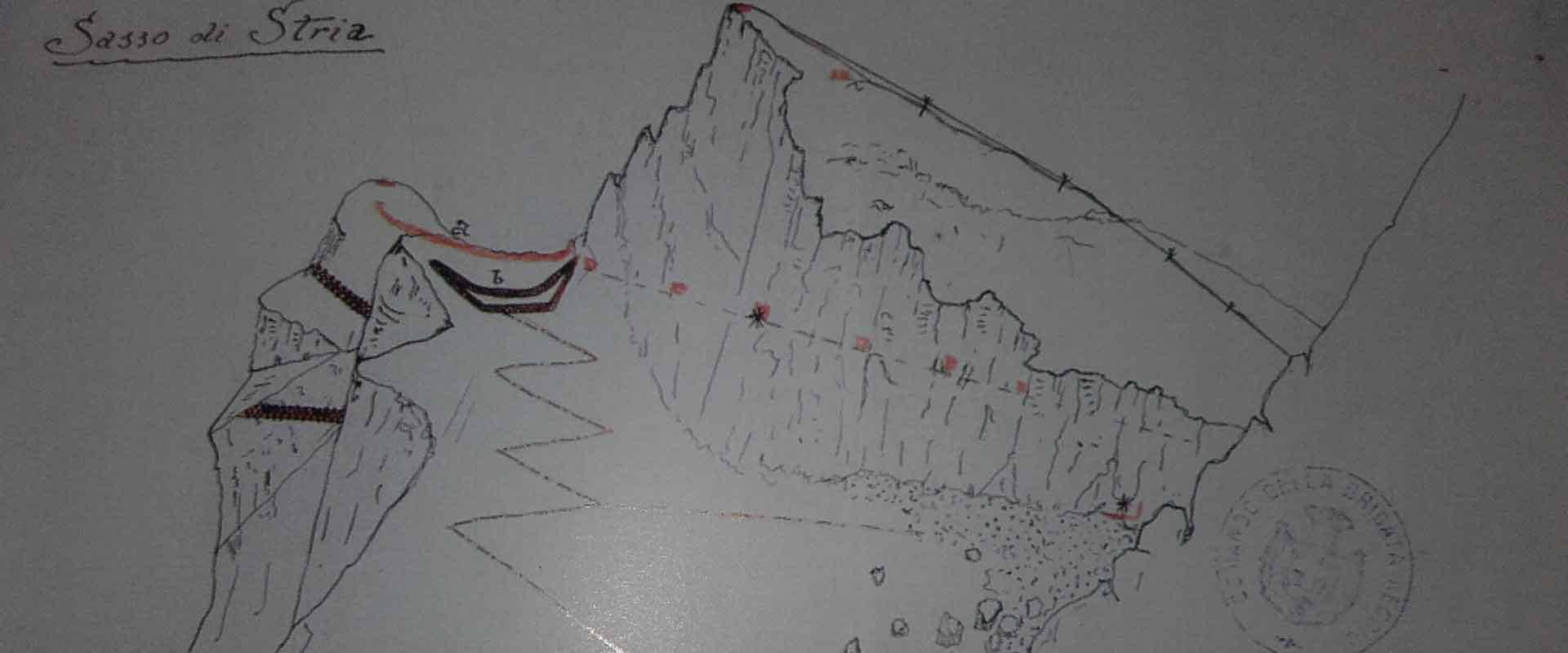

Since the passage through Valparola was barred, the Italians concentrated their efforts to the west, on the road to Bolzano and Trento.

For tactical reasons, it was necessary to conquer the surrounding peaks in order to enable the passage leading to South Tyrol and Trento. The first peak was the Col di Lana, in a direct line only two kilometres away from the Sasso di Stria.

To place a mine underneath the mountain top, the Italians dug a long tunnel and armed it with 5 tons of explosive, blowing it up on 17th April 1916. Half of the Austrian contingent was killed by the collapse of about 10,000 tons of rock (hence it was dubbed "Blood Mountain").

In order to control the mountain passes leading to the north and to the west, it was necessary to conquer the peak of Mt. Sief as well.

The attacks continued until October 1917, also here with a the explosion of a mine tunnel, but the Italians didn’t succeed in overcoming the Austro-Hungarian defence. The way towards Trentino remained barred.

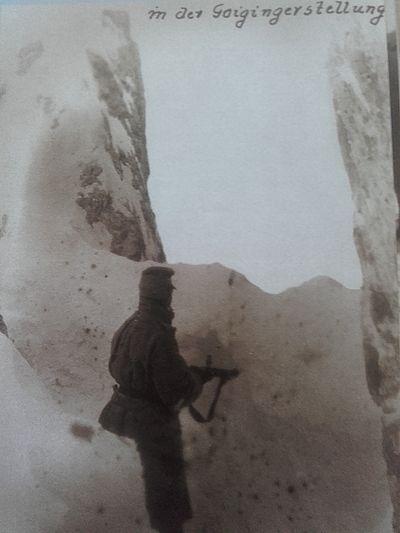

Lieutenant Malvezzi, who conceived the mines of the Castelletto and Mount Lagazuoi, in 1917 worked out the ambitious project of a tunnel with several branches, an entrance under the Goiginger emplacement, two mine chambers and two exits for the soldiers.

The mine chamber to the west was intended to blow up the Edelweiss emplacement, the second one, eastward, to take down the entrance of the Goiginger tunnel and thus interrupt the supply route to the saddle (Selletta).

However, this project was never realized because in November 1917, after the Battle of Caporetto, the Dolomite front was abandoned.